In 2013, while still at art college, I was shown Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore by one of my then tutors, Helen Johnson. This work had a large effect on me, as both an artist and as someone with their own history with the rave scene, albeit at a distance in both time and place to Leckey’s own.

As a younger artist I set out to make work like Leckey’s. Though it is perhaps not uninteresting that as I turned 35, the same age Leckey was when he made Fiorucci, I seemed to be have my own reckoning with the scene broadly known as rave, and too Leckey’s Fiorucci. Leckey’s work has always seemed to me a work about holding-on. The thing that it reaches for is that near moment of youth that the work gives image to. While I still find Leckey's work remarkable, the more I have watched the work the more it has filled me with a sense of looping stuck-ness. Stuck in the reach of its own ideas, of rave and hardcore.

I wanted to make a work that tried to move beyond this. If Leckey’s film was about trying to hold onto something which had been lost, I wanted to make a work about the possibilities of letting-go. One of the first decision I made in commencing this work was that there would be no rave music, and no use of the compositional techniques of rave. While I wanted to show my own reverence for this period, I also wanted to acknowledge that our ideas are fragile. The ideas we identify with, which give our lives meaning for a while, are prone to failure, to breaking down. Leckey's work occupys some point at the cusp of this breakdown. But how do we live well beyond the breakdown of our ideas? This is the question I am interested in.

With this work I looked to moments both before and after the peak of rave in the late 1980s and early 1990s, to assemble a sense of meaning in this movement that looked beyond its more recognisable elements. One of the central narratives this work was developed around was that of Sister Alicia, who cared for David Mancuso during his childhood at the Utica children’s home. When later Mancuso established the Loft, a venue seen now as one of the origin points of house music and the underground club, it was the children’s party room at the Utica orphanage that Mancuso worked to recall. This was an unexpected origin story for the later rave and electronica scenes, and an opportunity to reconsider their legacy. For Mancuso it was about the creation of a particular space, a room and its effects, which was bound up with an intergenerational thinking of love, tied to the figure of Sister Alicia—a love different from that characteristically associated with recent countercultural movements. This is where I started: like Mancuso, I began with the Utica party room and worked outwards from there.

This work was originally shown in 2020 across both Neon Parc's City and Brunswick gallery spaces, incorporating the 'Enjoy All Monsters' light series (seen in the preview above). It has subsequently been shown without these works in accompaniment.

Related works:

Enjoy All Monsters (2020)

3AM Eternal (2014)

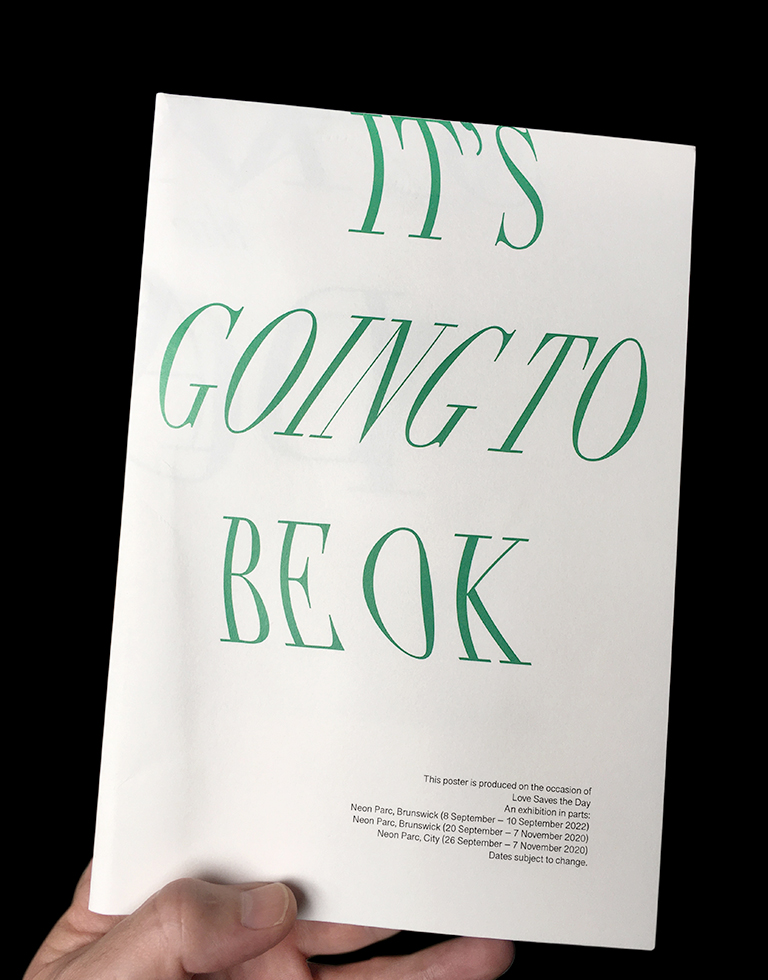

Love Saves the Day, poster multiple text transcript

1.

In the first image I see a boy of five or maybe six standing in the mid-afternoon sun. His eyes are pinched against the glare as are those of the boys around him. He does not smile. He, and they, wear their hair short, with white cotton shirts under corduroy bib-and-brace. It is the attire of boys in 1950s America. If Mancuso, who stands centre-frame, were allowed to grow his hair it promises a loose curl. It is unlikely people will have heard of David Mancuso, and more unlikely still that they would recognise him. This obscurity is one that he, in his adult life, worked hard to maintain. Though his story now is becoming more recognisable. His story which is also the story of Sister Alicia. Sister Alicia who stands some distance behind yet still within frame, with boys too gathered around her. Boys also in white shirts and corduroy, with high socks, black shoes, and tanned legs.

Chapter 1 (p.5-32) titled ‘beginnings’, details that when, years later, as a young man on Valentine’s Day 1970, Mancuso hosted the first of his Loft parties in the small loft-space of the North Huston warehouse he then occupied, a venue now recognised as an origin point of the underground club and dance music culture, it was the children’s party room at the Utica orphanage that Mancuso worked to recall. That room that he worked to recreate. The low ceilings, the lighting, the balloons and where, like Sister Alicia, Mancuso would set a table with food and drink. Sister Alicia would find every opportunity to host a party. A time of respite in an otherwise difficult circumstance. The invitation to Mancuso’s party carried the title Love Saves the Day. A mixed message. For while its initials, taking the first letter of each word, surreptitiously gestured at Mancuso’s practice of dosing the punch with LSD, it speaks also of the possibility of love.

And though Valentine’s Day, not the love of lovers but the love of a mother. Of a mother who was not a mother. Of the love of those who are not loved. Who, not being one’s own are harder to love. Of a mother who says: because they are not loved they must be loved. Or at least this I assume looking at the first of these two photographs.

Sister Alicia’s black serge tunic reaches the ground. It is autumn. The cornette atop her head, familiar as that of a sister of charity, known also for its winged shape as butterfly nuns, glows on the surface of the paper. Glows along with the white cotton of the boy’s shirts. So bright against the autumn sun above the playground that the film negative records no detail. Islands of light, an excess of lightness. Starched wings, so blessedly touched as to escape all record. A lightness at whose center there is no secret, the paper is merely paper. The sun merely the sun.

2.

In the second photo however, there are no butterflies. It is an image taken just before sleep. Iron beds line either side of the narrow dormitory. The children kneel, bunched together in the row formed between the feet of the beds. They uniformly face the camera. There is no sun, but a camera flash. The boys at the rear recede into an oily darkness, their silhouettes hard to decern. The boys at the front are bathed in a pulse of light. Round eyed, heavy little boys. Gathered together in prayer, squeezed together cheek-to-cheek in the narrow dorm, not butterflies but sardines. Creatures that swim brisk and free in every ocean of the world, under ice caps and up and down great canals. That swim in giant shoals off the coast of uninhabited islands, too. Creatures though much more readily imagined in cans. Oceanic, but no longer for the ocean. I ask myself, why does a figure like Mancuso emerge from a place like this? Is it that souls like his are destined for orphanages? Surplus. Excess to their community. Sent away to homes because they are not the kind of children that the world needs? Or is it rather that orphanages may harbour such souls? Harbour them until the conditions are right for them to re-emerge, shoals of them emerging from party rooms behind orphanages all over the globe! On clear nights for instance, or upon the solstice. Emerging briefly, only to disappear into similar rooms, similar rooms in other hard to find places. Not revolutionaries. Or if they are, they are the kind of revolutionaries who stay out of sight, and want no revolution at all.

Heavy little sardines, who until then wait, hands clasped, round lipped, bathed in a pulse of light, saying what? The Lord’s prayer, Give us this day our daily bread. Or perhaps, mouthing? Mouthing but not yet able to form the words, uttering them in the merest call: if I am here, in this can, a sardine who is given to speak, a sardine who can imagine a dance floor, who can go undetected in this place for years, and then when the time is right who can install Klipsch horns in a warehouse loft, and summon great shoals to party rooms, rooms in which we might glimpse our one true sardine nature, then many things are possible. One need only learn to track them! This is the thought I am left with looking upon the second of these two photographs. Go where they go. Move how they move. On each clear night staying from sight, learning to listen for sardine call and follow sardine track.

Notes on Tim Lawrence's ‘Love Saves the Day: a history of American dance music culture, 1970-1979’. Detailing two images which appear on consecutive pages, 6-7.

Jamie O'Connell. January 30, 2020